Having just returned from New York, where they took part in ECO-Solidarity, an event organized as part of Wanted Design Manhattan, Archibald Godts and his partner Theresa Bastek, the founders of Studio Plastique, look back on the event and the fundamentals of their project.

Archibald, you’re Belgian. And you, Theresa, are German. You met while studying at the Design Academy in Eindhoven. What drew you to the school, and how did you come to set up your studio?

Theresa: We had both just finished studying design. What interested us about the course was the experimental approach and the way in which design can be a vehicle for well-being. This very humanistic side of design is at the heart of our approach. We’re not just interested in form and aesthetics, but in the role that design plays in society, from the sourcing of materials to the end of the product cycle.

Tell us about the way you work.

Archibald: In the case of a project commissioned by a particular client, the first part of the job is to understand exactly what that client’s needs are and the reality of their business. You can have the best intentions in the world – in terms of sustainability, for example – but if the context of the request is global, it is necessary to take this reality into account when choosing manufacturing processes and modifying materials. In their search for solutions, designers are often faced with limits. Our aim is to try to push them back by making connections between contexts and materials.

You work for clients in a wide variety of fields, including fashion. Tell us about your recent collaboration with a luxury brand.

Archibald: The brand contacted us as part of a reflection, not on the product as such, but on the way in which it is presented in the shop windows. The design of these ephemeral spaces raises a whole series of questions, particularly in terms of choosing a type of material that is both aesthetically pleasing and suitable for ephemeral use, in the context of a global application. It’s all about striking a balance between these different parameters.

One of your projects led you to work with the Savonneries Bruxelloises.

Archibald: The Linen Lab, a project carried out in collaboration with scientists and researchers from different sectors, focused on geopolitical, economic and historical issues. The aim was to reflect on the cultivation, processing and use of flax in a new context. In the past, flaxseed oil was used in Belgium to make hygiene products. So it’s a question of thinking about how we can add value to a product. In this case, it led to the development of several products, including a solid body scrub.

Your research often takes the form of exhibitions, as was the case a few months ago at z33 in Hasselt. Can you explain?

It’s a project that questions the notion of energy. In our work as designers, it’s obviously very interesting to take an interest in a raw material that is intangible, but essential to our everyday lives. Thinking about how we can approach this driving force, which is also a source of problems (particularly in the context of global warming), is at the heart of our approach. By putting ourselves in the position of those who don’t have access to it (as is the case in some parts of the world), we are proposing ways of reinventing our relationship with electricity and the way we consume it. For our studio, this research, which we carry out at the invitation of certain institutions, is essential in that it often leads to more concrete collaborations.

You’ve just taken part in ECO-Solidarity. How was this event, which brought together young studios like yours, interesting in the context of a rather conventional design fair?

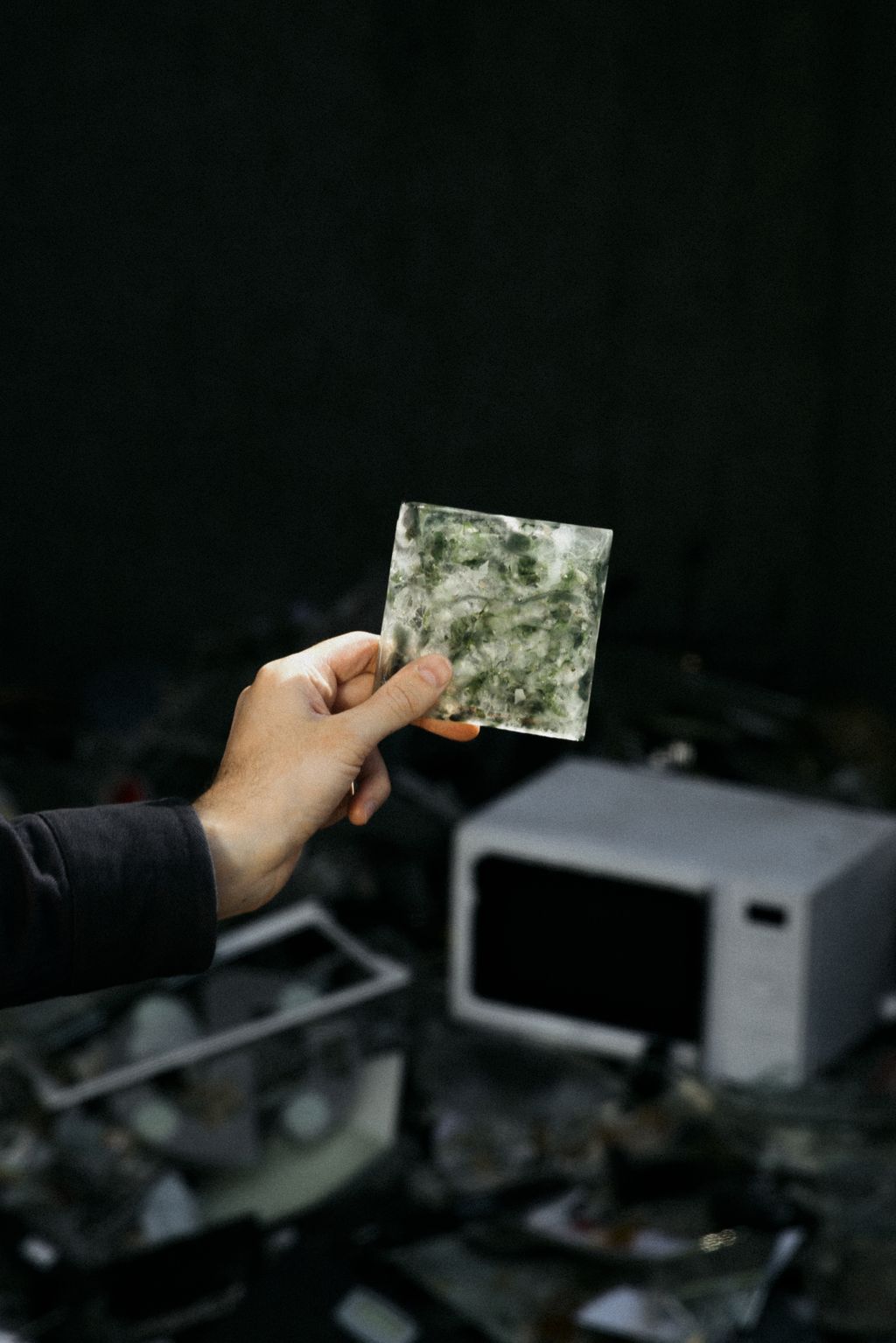

Theresa: It’s true that Common Sands, the project we presented in New York last May, was in stark contrast to the resolutely economic stakes of this fair. In this case, our research resulted in a collection of glass tiles made from components from discarded ovens. In an environment like that of the New York fair, this type of project has the merit of questioning the industry’s classic modes of operation.

After several years working in the studio, it’s once again possible to travel and present your work on another continent. Is this essential for you?

Theresa: The idea of travelling so far for such a short period of time obviously forced us to ask ourselves some questions about the relevance of such a move. But we think it’s both interesting and important to put our thinking into a context other than a strictly European one. In the United States, ecology is at the centre of debates, but concrete applications in industry are still slow to appear.