Duo Lidewij Edelkoort and Philip Fimmano are the curators of Belgium is Design’s new textile exhibition, The Gift to be Simple as part of the 7th New York Textile Month. Philip Fimmano travels the world in search of tomorrow’s trends for Trend Union alongside Li Edelkoort. We caught up with him on the eve of the festival.

From the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe (the largest folk art market in the world) to Paris, Philip Fimmano travels the world in search of tomorrow’s trends for Trend Union, alongside the company’s founder Li Edelkoort (the most militant of trend forecasters). We caught up with him on the eve of the 7th New York Textile Month, where this duo has brought together several Belgian designers in an exhibition for the Belgium is Design initiative.

What is your job?

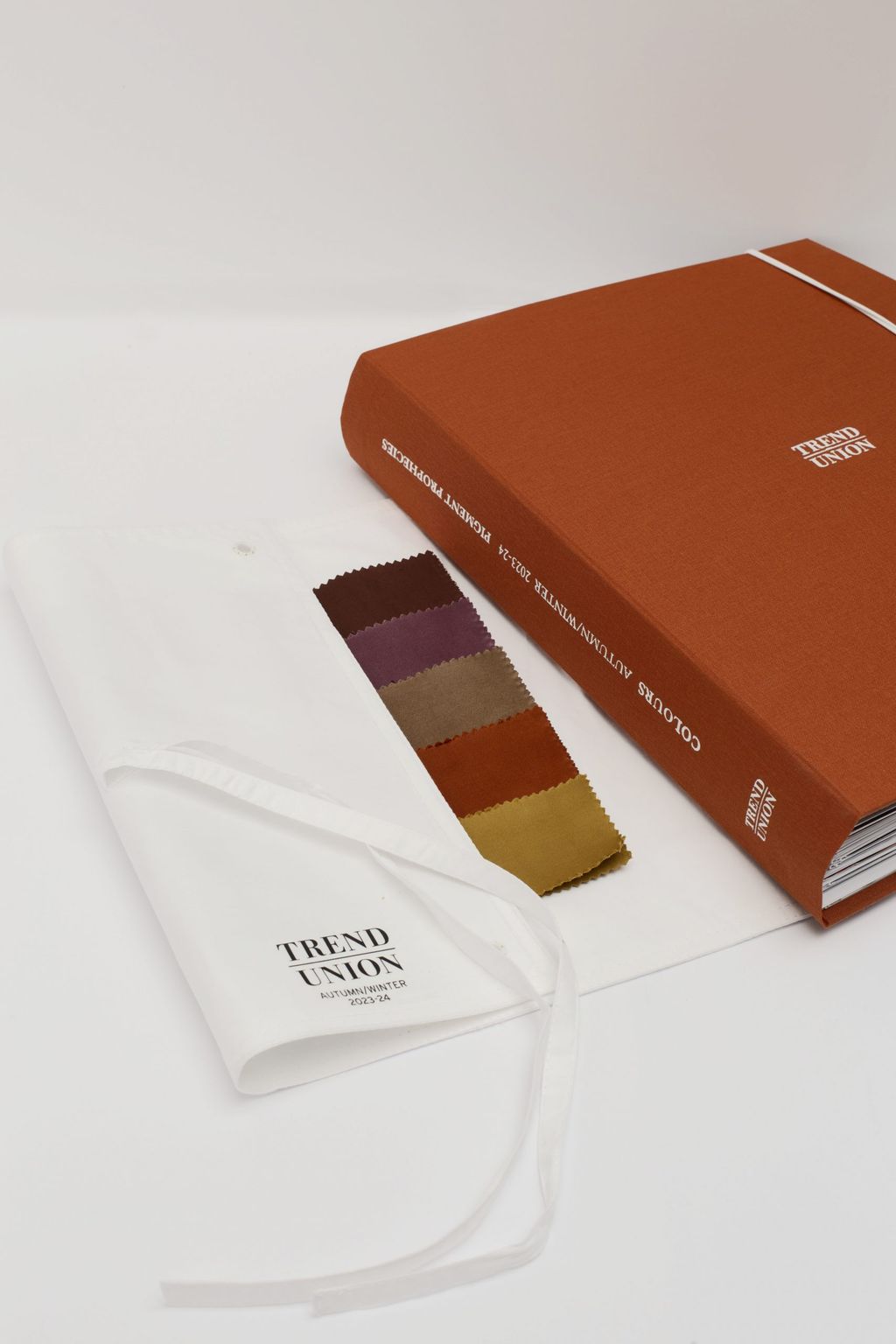

To advise and support brands in all areas of the creative industry in developing their products and services. Trend Union studies current trends in society, emerging and future creative currents and those that will last longterm. We produce trend tools based on these observations and our research. We also play an educational role with students and all those interested in creativity in general.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m working with Li Edelkoort on the new masters programme in textile design for the private Italian fashion school Polimoda, in Florence. It is called “Farm to Fabric to Fashion” and allows students to understand and revolutionise the manufacture of natural fibre textiles and clothing.

You have been promoting textile creativity with Li Edelkoort for several years; tell us about it.

Having opened several Trend Union offices (in Paris, New York and Tokyo), and since creating the agency in 1986, Li Edelkoort has advised the world’s most prominent design studios. She became interested in textile design as a design discipline in its own right, just like industrial design, which led us later to launch Talking Textiles. This international touring exhibition first presented at the Milan Furniture Fair in 2011 then prompted her to head up a department dedicated to textiles at Parsons School of Design in New York. Her initiative to foster the survival of craft and promote emerging talent and innovation in textiles has led to much deeper knowledge of the subject and respect for this sector, with a sustainable dimension, before the word was commonly used.

Is analysing and predicting trends different today?

The world has changed dramatically and there are real opportunities to do things differently, especially in terms of sustainability, but in the face of that, our business hasn’t really changed. This is why we offer encouraging ideas for reflection, to contribute to change and the evolution of society. This is also why we created the World Hope Forum: a series of free and inspiring online monthly conferences; because we believe that taking advantage of the “positive” around us instead of the “negative” is beneficial for design.

One of the features of Trend Union is its holistic vision. Why?

We approach trends holistically and this allows us to prescribe original ideas at different stages of a project, and lets our clients be independent by not inundating them with lots of divergent information, but instead offering them a very precise vision of tomorrow’s trends.

Explain why you believe in the longevity of trends, rather than their volatility.

We believe that trends are things that are embedded in society over the long term, for decades. Seasonal fashion presentations are a thing of the past, and this is one example of the debates brought about by Li Edelkoort’s “Anti Fashion” manifesto.

Are trends now more receptive to society in the age of social networks?

Trends exist before influencers relay them on digital platforms. These platforms do not change the fate of the trends but rather feed them. This is why we differentiate betweentrend watching, which may require exploring social networks, andtrend forecasting, which projects us two to three years into the future with advanced thinking, beyond the usual spheres of information. Also, external events are only triggers. This is obvious with the Covid-19 pandemic, which has changed the way we live permanently, but everything we consider to be phenomena, such as the evolution of conscious consumption, was already on its way.

How do brands assimilate trends?

Translating trends into products requires them to use a range of aspects over an incompressible amount of time, hence the existence of freelance consultants and designers as well as marketing strategists. In addition to our work, which presents several trend themes each season, a brand sometimes asks us to collaborate directly to select colours for its materials or interpret our trend books in connection with their research and development.

What have you learned from the textile designers you have met so far?

First of all, the global textile community is much larger than we imagined 20 years ago. To understand the world of textiles in depth, we went to places that are sometimes very isolated, to India, Tibet, Japan, South Africa and Peru, where artisans honour indigenous cultures by practicing age-old techniques. Textiles are a real common thread for understanding our lifestyles because they are linked to anthropology.

How do you reflect these sometimes ancestral forms of creation?

Design often omitted the history of some of these cultures in its formation and we are trying to correct this. But education takes time. So, after starting our Talking Textiles initiative (in reaction to several weaving mills and spinning mills closing in Europe and the United States), we decided to launch New York Textile Month, so that the public could see the value and diversity of textiles and invest in their preservation and future.

This is the second time you have brought Belgian textile designers together in New York. What is so special about them?

“The Gift to be Simple” group exhibition for Belgium is Design is the second event we have organised to promote the Belgian textile industry during New York Textile Month. It is a return to the origins of the beauty of natural fibres, the raw character and tactility of textiles, and more generally the spirit of simplicity that everyone searches for today. Our call for projects for this led to the curation of a group of designers whose creations offer a new and sensitive experience of textiles and objects.

In Belgium, there is strength in women’s textile design. What are the common traits of the designers attending for this event?

Natalia Brilli, Emma Cogné, Laure Kasiers, Charlotte Lancelot, Geneviève Levivier, Céline Vahsen, Alexia de Ville, Vanessa Colignon, founder of the brand the Design for Resilience and Pascale Risbourg, which transforms its textile patterns into objects, have their own styles and objectives. Some create using recycled elements, others reduce their environmental impact… but they all manufacture in Belgium, with wool, raffia, even paper, and take advantage of the inherent properties of the materials, such as the sound insulation and thermal regulation specific to linen.

What do you think characterises Belgian design?

The Belgian landscape and its rural aspects, marked by the history of the spinning millsand industrialisation; this is perhaps why Belgian designers often follow through with their ideas, producing locally and with a strong desire for materiality and purity, accentuated by the use of organic materials that provide warmth, such as wood and natural stone. They are very open people, receptive to the environment around them and to other neighbouring cultures, which means that they perfectly understand our era.