The Belgian duo Unfold, who were named ‘Designer of the Year’ five years ago, are continuing their unique exploration of design through digital design and under the spectrum of history. Between their collaborations with the luxury and beauty industries, they are inaugurating the final chapter of their ‘Atlas of Lost Finds’ project, which is taking them to the Amazon.

Claire Warnier, who co-founded the studio with Dries Verbruggen, explains this adventure.

You co-founded Unfold Design Studio twenty years ago. What stands out from your experiences so far?

Our dynamic has evolved since 2002 and our work has improved considerably when it comes to precision. Over the years, we have found a balance between projects for the general public and other more experimental projects that works for us. We evolved in the Dutch creative tradition established by Droog Design, which linked the conceptual and the industrial, and our studies in The Netherlands, at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, taught us to retain our autonomy and defend our artistic vision with clients for marketing and commercial purposes.

What have you observed in the world around you since then?

In the meantime, the world has changed and the climate crisis has emerged. Producing something is no longer as trivial as it used to be and each production should ideally be meaningful or call for positive action that benefits the environment or society. The shift in how designers think is now a fact: young designers are no longer as eager to launch their own studios. As a result, they begin by working together as a collective, or joining companies to train on the job.

With the benefit of hindsight, how would you summarise the raison d’être of Unfold today?

We offer an artistic approach to artisanal, industrial and stage design, from manufacturing to distribution, with a link to social issues or the history of objects. In the early 2000s, we were initially interested in how we could transpose digital creations into the real world. This was not so easy at the time – 3D printers were expensive and just emerging, as were open-source machines.

What is the advantage of working as a duo?

We form a tandem in which we both complement each other, especially when we are striving to create sophisticated temporary installations, such as the layout of the windows for Hermès. Generally speaking, I look at the big picture, while Dries focuses on the details. For our first project for the brand in 2020, we took liberal inspiration from our collection of furniture, tableware and lights based on 3D-printed structures and artisanal expertise such as glass-blowing. This collection was called ‘Skafaldo’ (2015–2017). From this, we were able to create installations from supports that we developed from both computer-generated images and paper straws. We are motivated by collective intelligence and appreciate the Hermès tradition, which uses and encourages craftsmanship in a contemporary manner.

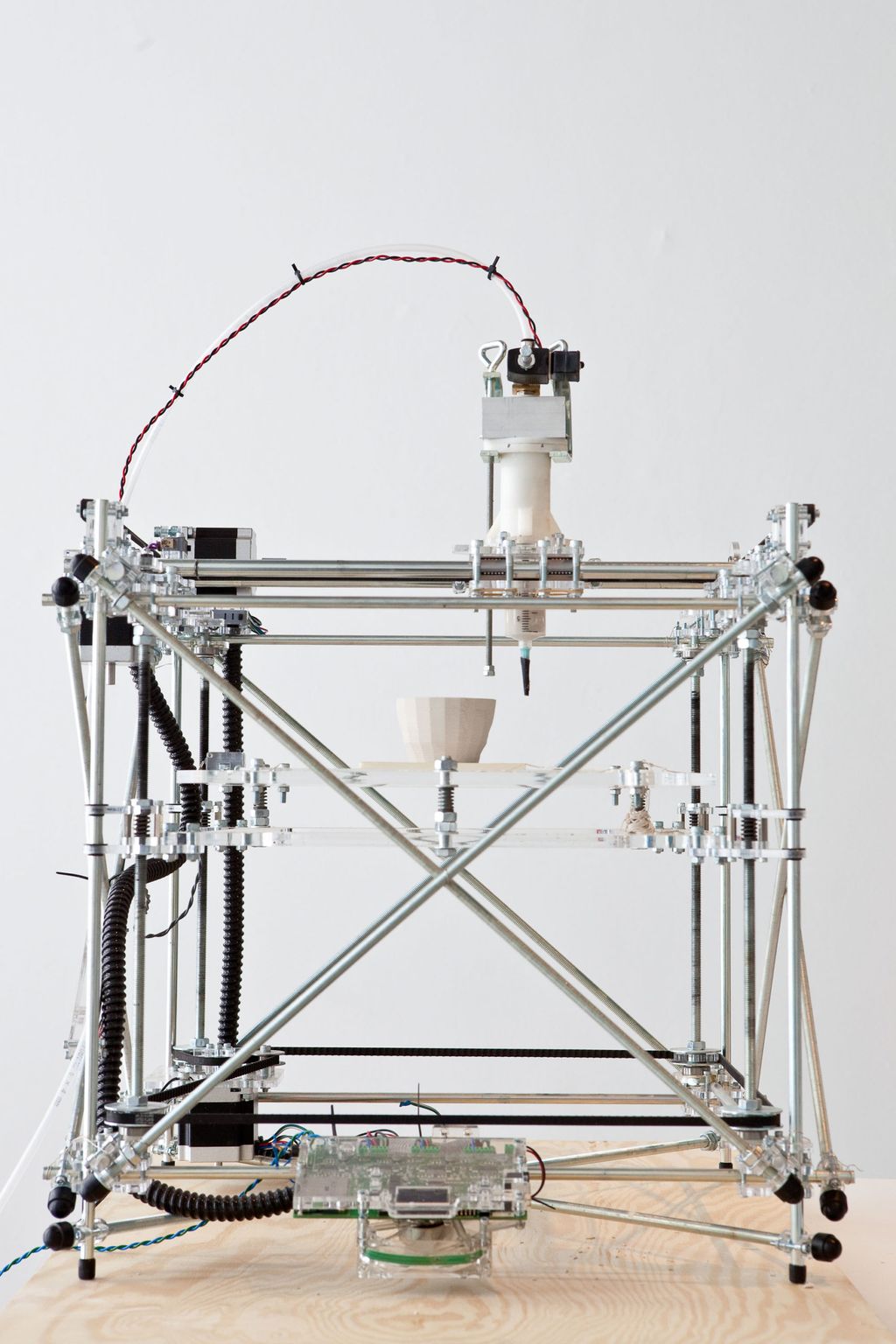

How have you helped to develop 3D-printing technology?

I discovered this technology while I was studying. Dries, for his part, has always been fascinated by new digital and open-source technologies. Open-source printers were how we were able to understand the flip-side of this technology, so that we were able to use it more effectively and, as a result, create new forms from that. To that end, we started by adapting the open-source development kit for a 3D printer with a view to printing clay. We also started by developing our own software programs, in order to use 3D printing in a new way. This opened up new avenues for us when 3D printing became more popular and gradually became more freely available.

Some of your work has been acquired by major museums. What does that recognition mean for you?

Confidence in what we set out to achieve, for sure. We are both proud of this because these are pieces that will be preserved over time and which will become templates for other artists. The first of three editions of the side table from the Skafaldo collection (2015), which was produced in collaboration with the Belgian company Materialise (a pioneer in 3D printing services), is a good example of this. It was recently acquired by the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris, the Centre Pompidou.

Why do you think your work has received international success since your project “L’Artisan Électronique”?

When that project — a digital version of the traditional ceramics workshop — was presented to the public in 2010, craftsmanship and industrialisation were seen as polar opposites in the design community. By working with the artist and designer Tim Knapen, who lives and works in Antwerp, as we do, we have discovered manual and computer-assisted ways of doing things that do not limit us. In order to produce this installation (which went on to tour the world), we simply based our approach on the way in which people have been designing pottery for thousands of years, by studying their gestures and considering how to transpose them to a fully digital tool. The concept of immateriality has been widely discussed since and is a big part of public debate. In this way, I think that our productions are a major source of inspiration because they reflect moments from our era and transitions that we, as humans, are going through.

What projects are you working on at the moment?

We have just finished a new project for Hermès and we are currently working on the renovation of the Design Museum in Ghent, where we are making the entrance gate. Finally, we are circling back to the study of artefacts with ‘Atlas of Lost Finds’, an itinerant creation that uses digital technology to design (or redesign) historic items that have been completely destroyed or altered, in order to keep their memory alive and convey the knowledge that goes with them.

Why has the theme of history been so important to you since your work “Artefacts of a New History”?

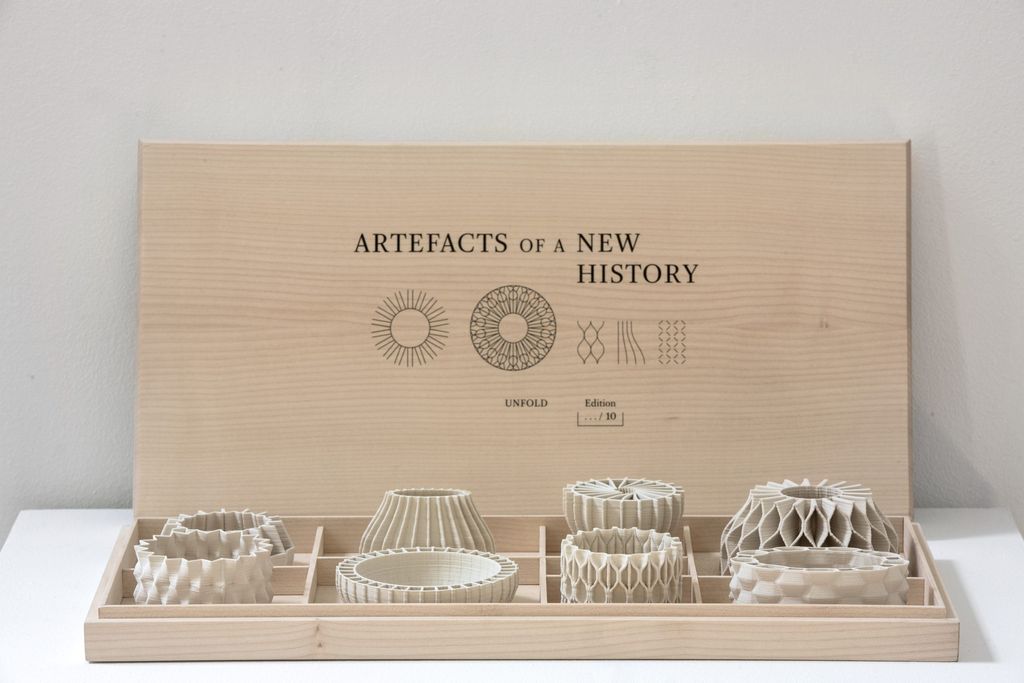

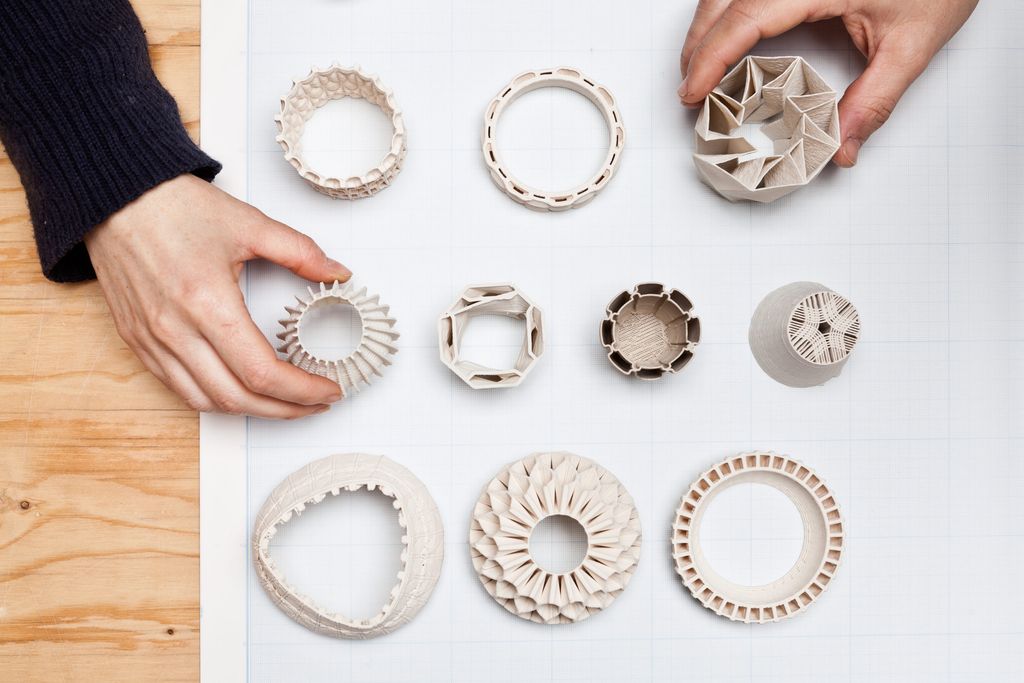

Firstly, I am fascinated by history personally and, as a creative person, how I refer to it. Once I finished my studies at the Design Academy of Eindhoven, I studied Art History at the University of Ghent. When we created our first ceramics with Dries, we almost always referred to ancient forms. Artefacts of a New History, which was produced in 2016 and sold by the Valerie Traan gallery and comprised a cabinet of nine miniature 3D prints that evoked utopian biomorphic buildings and artefacts that could be seen in museums, or even fossils from archaeological sites, was the most convincing result. Thanks to that, we have discovered how complex the most common and ancient geometric shapes are, despite these sometimes appearing to be the simplest.

Tell us about the genesis of ‘Atlas of Lost Finds’ and your work to safeguard indigenous artefacts?

Before we started this project, we were in contact with a scientist from the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, who spoke to us on a regular basis about the digitisation of items from the institution’s collection by the museum’s laboratory: palaeontological and classical archaeological items and remarkable artefacts and works from Amerindian civilisations. In 2018, when the museum burned down in a fire, 18 million items out of 20 million were lost. We contacted him to find out what he was going to do with the scans of these items. In order to bring these lost collections back to life through digital design, we launched the Atlas of Lost Finds call for projects on the Wikifactory social platform, which makes it possible to begin production in a collaborative manner. The first file that we gave free access to was the scan of a Peruvian Filideo stirrup from the pre-Colombian Chimú culture (1,000–1,470). This project was launched during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and, thankfully, we were surprised by the general enthusiasm! More than 30 international designers have joined us on this adventure. The result of these experiments can now be viewed online on the ‘Atlas of Lost Finds’ website.

That raises questions about the future of heritage and the reappropriation of History…

The first result of this project has proven two things: that digital technology is a unifying force and takes people to new places, and that it is possible to use digital data in a meaningful way to create new items and reframe history from a ‘decolonised’ point of view. For the second phase of Atlas of Lost Finds, we relied on ceramic urns from the lost Marajoara culture in the Amazon, which were acquired by Western museums. An initial copy of this item was identified in Antwerp at the Museum aan de Stroom (MAS). This was offered to the Flemish government by the heirs to the Janssen family of pharmaceutical engineers. We got permission to scan this urn and other similar pieces belonging to European institutions, like the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. We will travel to the Amazon this summer to recreate them, at the site where these urns were originally created. This is the island of Marajó, where no indigenous people live today, although the Marajoara ceramic style has become popular. As a result, a new version of the Marajoara urn will be produced from the digital print that captured its original shape by ceramic artists from the region.

What will happen to this new artefact?

In order to keep track of this work, we are working with director Alexandre Humbert, who created the short film The object becomes. (2021) for Belgium is Design. We will travel to Brazil with him, in order to describe the origins of the Marajoara urn and contextualise it because the new version of this urn will be buried in the Amazon rainforest. We have already collaborated with Alexandre on A Combmaker’s Tale (2020), a series of films that tells the story of the last remaining combmaker in Croatia and their work, as well as the robot who is taking over from them to preserve their expertise.